mortuary temple of Amenhotep III

Kom el-Hetan

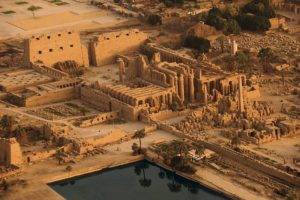

The mortuary temple of Amenhotep III, located on the West Bank, was once the largest temple of its time, covering 350 thousand square meters. It stood out as one of the grandest religious structures in Egypt during the 18th Dynasty, surpassing even the famous Temple of Amun at Karnak. Today, it is known as Kom el-Hetan, situated about half a kilometer southeast of Medinet Habu. This sprawling site stretches from the Colossi of Memnon to the bend near the Antiquities Inspectorate.

Sadly, Amenhotep’s mortuary temple didn’t stand the test of time, likely due to the high water content in the soil. Until recently, only the Colossi of Memnon—two giant statues of the pharaoh—remained to mark the entrance. By the 19th Dynasty, many of the temple’s blocks had been reused by Merenptah for his nearby funerary monument.

The temple’s layout is known thanks to the traces of pylons and columns that have been buried for centuries. It was once listed among Petrie’s ‘Six Temples at Thebes,’ though it was never thoroughly excavated until recent efforts by German and Egyptian archaeologists. These excavations have revealed fragments of architecture, including a columned hall at the temple’s rear.

The temple housed numerous freestanding statues, sphinxes, and massive steles, once adorned with descriptions of Amenhotep III

Luxor Tours & Activities

Looking to save some costs on your travel? Why not join a shared group tour to explore Luxor, Egypt? Here are some activities you might be interested in:

The temple entrance faced east toward the Nile, directly opposite Luxor Temple. Flanked by two massive statues of Amenhotep III, smaller statues of Queens Tiye and Mutemwiya were placed at their feet. The temple featured two large courts and three pylons, adorned with seated statues of the king. Near the second mudbrick pylon, excavators found a headless sphinx statue of Queen Tiye, jackal statues, and Osirid statues of the king. In 1957, a headless sphinx with the body of a crocodile was discovered at the southern side of the temple site, still visible today along with many other recent finds.

An avenue of sphinxes led from the third pylon to a solar court surrounded by sandstone papyrus columns and Osirid statues of Amenhotep III. The statue bases listed captives from foreign lands, offering insights into Egypt’s interactions with other countries. At the south entrance to the solar court, a large quartzite stela has been re-erected, depicting the king with Queen Tiye and the god Ptah-Sokar-Osiris. Below the stela are texts detailing the king’s building achievements. A similar stela once stood at the north entrance but is no longer there.

The inner chambers of the temple are largely destroyed, but many bases of limestone papyrus columns have been uncovered. Much of Amenhotep’s temple was repurposed for the Temple of Merenptah, with recent restoration efforts shedding new light on Kom el-Hetan based on original block decorations. The temple was dedicated to the god Amun-Re, with a smaller northern temple dedicated to Ptah-Sokar-Osiris. Fragments of Amenhotep’s blocks and statues have also been found in various temples on both the West and East Banks.

by: Hourig Sourouzian

Amenhotep, son of Hapu, served as the chief architect and held such a prestigious position that he was granted his mortuary temple near Medinet Habu. He was later deified in Ptolemaic times. The temple’s unique design placed parts of it in the Nile floodplain, causing areas to flood during inundation. The rear chambers, including the sanctuaries, were built on higher ground, likely remaining above water. This design may have been inspired by the creation myth, where the mound emerged from swamp waters after the inundation. The extensive use of mudbrick likely accelerated the temple’s decline.

A unique feature of Amenhotep’s temple was its abundance of statuary. It included a standing and seated statue of the goddess Sekhmet for each day of the year, as mentioned in ancient texts, creating a ‘Litany of Sekhmet.’ Many of these Sekhmet statues still stand around Thebes, especially in the Temple of Mut and other Karnak temples. Many sculptures were later repurposed by other pharaohs for their monuments.

In 1998, Kom el-Hetan was listed by the World Monuments Watch as one of the world’s 100 most endangered monuments. Since the 1970s, German-Egyptian teams have uncovered numerous objects and architectural elements, cleaned, restored, and displayed on concrete pedestals, transforming the area into an open-air museum. In April 2002, archaeologists discovered three large statue fragments at the second pylon site: the right half of a red granite colossal seated statue of Amenhotep III, the head of a queen wearing a pharaonic headdress with uraeus, and an unidentified pair of legs on a rectangular pedestal.

In 2009, the colossal fallen statue of Amenhotep III was reconstructed and raised again at Kom el-Hetan. The statue’s head, taken to the UK in the 19th century by antiquities collector Henry Salt and housed in the British Museum, was replicated and returned to complete the statue. Other large parts of the limbs and torso have been found during excavations led by Dr. Hourig Sourouzian of the Armenian Academy of Sciences. The granite statue originally belonged to a pair in the peristyle court, with the king wearing the red crown of Lower Egypt, while its companion wore the white crown of Upper Egypt.

by: Hourig Sourouzian

In March 2009, Dr. Sourouzian’s team reported two more statue finds: a well-preserved black granite seated statue of the king on a throne and a quartzite sphinx depicting Amenhotep III. Both statues are largely well-preserved except for minor damages.

by: Hourig Sourouzian

In March 2010, a massive granite head of Amenhotep III wearing the white crown of Upper Egypt was discovered. Despite the missing royal beard, the head is one of the best-preserved likenesses of Amenhotep III, with finely carved features, polished smooth, and traces of red paint on the uraeus.