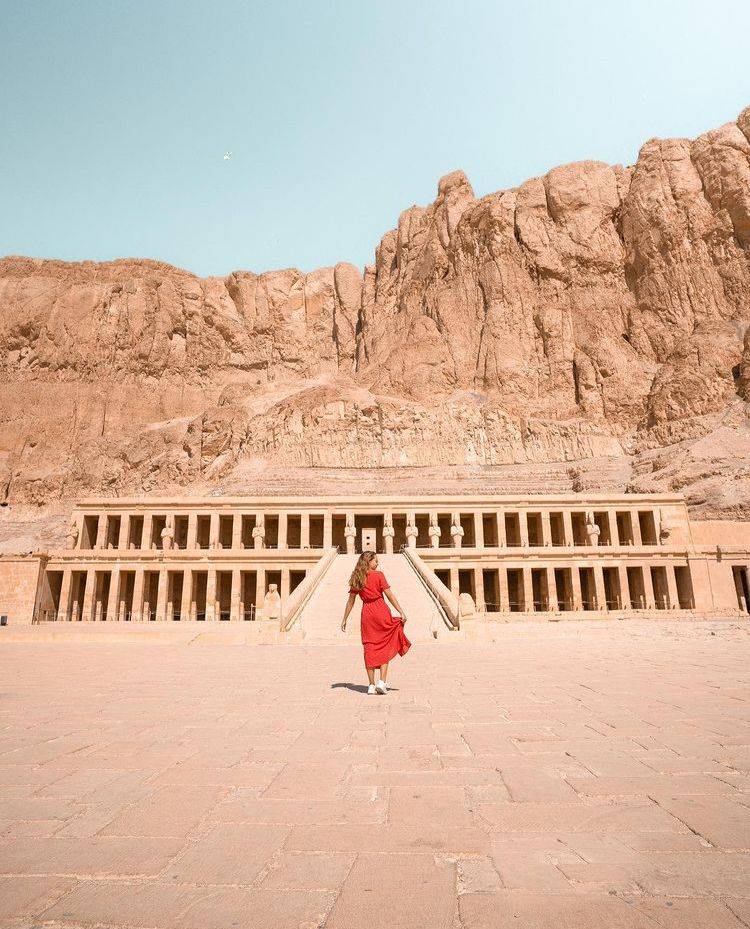

Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut

Djeser-Djeseru “Holy of Holies”

Temple of Hatshepsut is a mortuary temple built during the reign of Pharaoh Hatshepsut of the Eighteenth Dynasty. It is considered to be a masterpiece of ancient architecture. Its three massive terraces rise above the desert floor and into the cliffs of Deir el-Bahari. The temple’s twin functions are identified by its axes: on its main east-west axis, the temple served to receive the barque of Amun-Re at the climax of the Beautiful Festival of the Valley, while on its north-south axis it represented the life cycle of the pharaoh from coronation to rebirth. At the edge of the desert, 1 km (0.62 mi) east, connected by a causeway lies the accompanying valley temple. Across the river Nile, the whole structure points towards the monumental Eighth Pylon, Hatshepsut’s most recognizable addition to the Temple of Karnak.

Construction of the terraced temple took place between Hatshepsut’s seventh and twentieth regnal year, during which building plans were repeatedly modified. In its design it was heavily influenced by the Temple of Mentuhotep II of the Eleventh Dynasty built six centuries earlier. In the arrangement of its chambers and sanctuaries, though, the temple is wholly unique. The main axis, normally reserved for the mortuary complex, is occupied instead by the sanctuary of the barque of Amun-Re, with the mortuary cult being displaced south to form the auxiliary axis with the solar cult complex to the north.

Separated from the main sanctuary are shrines to Hathor and Anubis which lie on the middle terrace. The porticoes that front the terrace here host the most notable reliefs of the temple. Those of the expedition to the Land of Punt and of the divine birth of Hatshepsut, the backbone of her case to rightfully occupy the throne as a member of the royal family and as godly progeny. Below, the lowest terrace leads to the causeway and out to the valley temple. The temple was designed by Hatshepsut’s steward and confidante Senenmut, who was also tutor to Neferu-Ra and, possibly, Hatshepsut’s lover. Senenmut modeled it carefully on that of Mentuhotep II but took every aspect of the earlier building and made it larger, longer, and more elaborate.

One of the incomparable monuments of ancient Egypt

Luxor Tours & Activities

Looking to save some costs on your travel? Why not join a shared group tour to explore Luxor, Egypt? Here are some activities you might be interested in:

Terrace Ramp

The opening feature of the temple is the three terraces fronted by a portico leading up to the temple proper, and arrived at by a 1 km (0.62 mi) long causeway that led from the valley temple. Each elevated terrace was accessed by a ramp which bifurcated the porticoes. The lower terrace measures 120 m (390 ft) deep by 75 m (246 ft) wide and was enclosed by a wall with a single 2 m (6.6 ft) wide entrance gate at the centre of its east side. This terrace featured two Persea (Mimusops schimperi) trees, two T-shaped basins which held papyri and flowers, and two recumbent lion statues on the ramp balustrade. The 25 m (82 ft) wide porticoes of the lower terrace contain 22 columns each, arranged in two rows, and feature relief scenes on their walls. The south portico’s reliefs depict the transportation of two obelisks from Elephantine to the Temple of Karnak in Thebes, where Hatshepsut is presenting the obelisks and the temple to the god Amun-Re. They also depict Dedwen, Lord of Nubia and the ‘Foundation Ritual’. The north portico’s reliefs depict Hatshepsut as a sphinx crushing her enemies, along with images of fishing and hunting, and offerings to the gods. The outer ends of the porticoes hosted 7.8 m (26 ft) tall Osiride statues.

The middle terrace measures 75 m (246 ft) deep by 90 m (300 ft) wide fronted by porticoes on the west and partially on the north sides. The west porticoes contain 22 columns arranged in two rows while the north portico contains 15 columns in a single row. The reliefs of the west porticoes of this terrace are the most notable from the mortuary temple. The south-west portico depicts the expedition to the Land of Punt and the transportation of exotic goods to Thebes. The north-west portico reliefs narrate the divine birth of Hatshepsut to Thutmose I, represented as Amun-Re, and Ahmose. Thus legitimizing her rule both by royal lineage and godly progeny. This is the oldest known scene of its type. Construction of the north portico and its four or five chapels was abandoned prior to completion and consequently it was left blank. The terrace also likely featured sphinxes set up along the path to the next ramp, whose balustrade was adorned by falcons resting upon coiled cobras. In the south-west and north-west corner of the terrace are the shrines to Hathor and Ra, respectively.

The upper terrace opens to 26 columns each fronted by a 5.2 m (17 ft) tall Osiride statue of Hatshepsut. They are split in the centre by a granite gate through which the festival courtyard was entered. This division is represented geographically, too, as the southern colossi carry the Hedjet of Upper Egypt, while the northern colossi bear the Pschent of Lower Egypt. The portico here completes the narrative of the preceding porticoes with the coronation of Hatshepsut as king of Upper and Lower Egypt. The courtyard is surrounded by pillars, two rows deep on the north, east and south sides, and three rows deep on the west side. Eight smaller and ten larger niches were cut into the west wall, these are presumed to have contained kneeling and standing statues of Pharaoh Hatshepsut. The remaining walls are carved with reliefs. The Beautiful Festival of the Valley on the north, the Festival of Opet on the east, and the coronation rituals on the south. Three cult sites branch off from the courtyard. The sanctuary of Amun lies west on the main axis, to the north was the solar cult court, and to the south was chapel dedicated to the mortuary cults of Hatshepsut and Thutmose I.

The temple was designed by Hatshepsut’s steward and confidante Senenmut, who was also tutor to Neferu-Ra and, possibly, Hatshepsut’s lover.

Chapel of Anubis

The chapel of Anubis is located at the north end of the second level of Hatshepsut’s mortuary temple. Anubis was the god of embalming and the cemetery. He was frequently represented with the body of a man and the head of a jackal, as he is shown here. Anubis sits on a throne, which, in turn, rests on a small plinth. He faces a pile of offerings which reaches in eight levels from the bottom to the top of the register. Although much of the color is now gone, one can imagine the vibrancy of the original painting. The Egyptians used mineral pigments; so the colors have not faded as much as vegetable pigments would have.

Chapel of Hathor

At the south end of the middle terrace is a shrine dedicated to the goddess Hathor. The shrine is separated from the temple and is accessed by a ramp from the lower terrace, although an alternate entrance existed at the upper terrace. The ramp opens up to a portico adorned with four columns carrying Hathor capitals. The walls of the entrance contain scenes of Hathor being fed by Hatshepsut. Inside are two hypostyle halls, the first containing 12 more columns and the second containing 16 columns. Beyond this are a vestibule containing two more columns and a double sanctuary. Reliefs on the walls of the shrine depict Hathor with Hatshepsut, the goddess Weret-hekhau presenting the pharaoh with a Menat necklace, and Senenmut. Hathor holds special significance in Thebes, representing the hills of Deir el-Bahari, and also to Hatshepsut who presented herself as a reincarnation of the goddess. Hathor is also associated with Punt, which is the subject of reliefs in the proximate portico.

Amun shrine

Situated at the back of the temple, on its main axis, is the climactic point of the temple, the sanctuary of Amun, to whom Hatshepsut had dedicated the temple as ‘a garden for my father Amun’. Inside, the first chamber was a chapel which hosted the barque of Amun and a skylight that allowed light to flood onto the statue of Amun. The lintel of the red granite entrance depicts two Amuns seated upon a throne with backs together and kings kneeling in submission before them. A symbol of his supreme status in the sanctuary. Inside the hall are scenes of offerings presented by Hatshepsut and Thutmose I, accompanied by Ahmose and Princesses Neferure and Nefrubity, four Osiride statues of Hathsepsut in the corners, and six statues of Amun occupying the niches of the hall. In the tympanum, cartouches containing Hatshepsut’s name are flanked and apotropaically guarded by those of Amun-Re. This chamber was the end point of the annual Beautiful Festival of the Valley.

The second chamber contained a cult image of Amun, and was flanked either side by a chapel. The north chapel was carved with reliefs depicting the gods of the Heliopolitan Ennead and the south chapel with the corresponding Theban Ennead. The enthroned gods each carried a was-sceptre and an ankh. Presiding over the delegations, Atum and Montu occupied the end walls. The third chamber contained a statue around which the ‘Daily Ritual’ was also performed. It was originally believed to have been constructed a millennium after the original temple, under Ptolemy VIII Euergetes, giving it the name ‘the Ptolemaic Sanctuary’. The discovery of reliefs depicting Hatshepsut evidence the construction to her reign instead. The Egyptologist Dieter Arnold speculates that it might have hosted a granite false door.

Solar cult court

The solar cult is accessed from the courtyard through a vestibule occupied by three columns in the north side of the upper terrace courtyard. The doorjamb of the entrance is embellished with the figures of Hatshepsut, Ra-Horakty (Horus) and Amun. The reliefs in the vestibule contain images of Thutmose I and Thutmose III. The vestibule opens up to the main court which hosts a grand altar open to the sky and accessed from a staircase in the court’s west. There are two niches present in the court in the south and west wall, the former shows Ra-Horakthy presenting an ankh to Hatshepsut and the latter contains a relief of Hatshepsut as a priest of her own cult. Attached to the court was a chapeled which contained representations of Hatshepsut’s family. In these, Thutmose I and his mother, Seniseneb are depicted giving offerings to Anubis, while Hatshepsut and Ahmose are depicted giving offerings to Amun-Re.

Mortuary cult complex

Situated in the south of the courtyard was the mortuary cult complex. Accessed through a vestibule adorned with three columns are two offering halls oriented on an east-west axis. The northern hall is dedicated to Thutmose I, the southern hall is dedicated to Hatshepsut. Hatshepsut’s offering hall emulated those found in the mortuary temples of the Old and Middle Kingdom pyramid complexes. It measured 13.25 m (43.5 ft) deep by 5.25 m (17.2 ft) wide and had an vaulted ceiling 6.35 m (20.8 ft) high. Consequently, it was the largest chamber in the whole temple. Thutmose I’s offering hall was decided smaller, measuring 5.36 m (17.6 ft) deep by 2.65 m (8.7 ft) wide. Both halls contained red granite false doors, scenes of animal sacrifice, offerings and offering-bearers, priests performing rituals, and the owner of the chapel seated before a table receiving those offerings. Scenes from the offering hall are direct copies of those present in the Pyramid of Pepi II, from the end of the Sixth Dynasty.

F.A.Q

7:00 AM- 5:00 PM Every Day

Adults: 160 EGP / Student: 80 EGP

Deir al-Bahari, on the west back of Luxor.

The temple was commissioned in 1479 BCE and took around 15 years to complete.

Senenmut, Overseer of Works Hapuseneb, High Priest. He designed it carefully based on the Temple of Mentuhotep II but he made every single aspect even larger.